michael stradley

AUGURY

Will Be — Is — Was

After the torch-light red on sweaty faces

After the frosty silence in the gardens

After the agony in stony places–T.S. Eliot, from The Waste Land

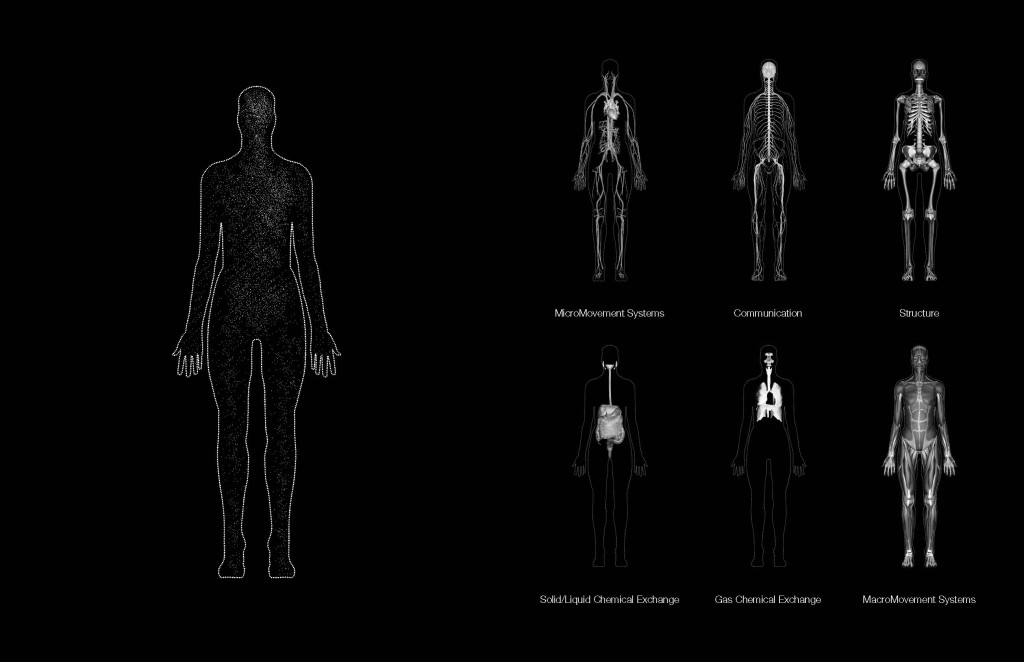

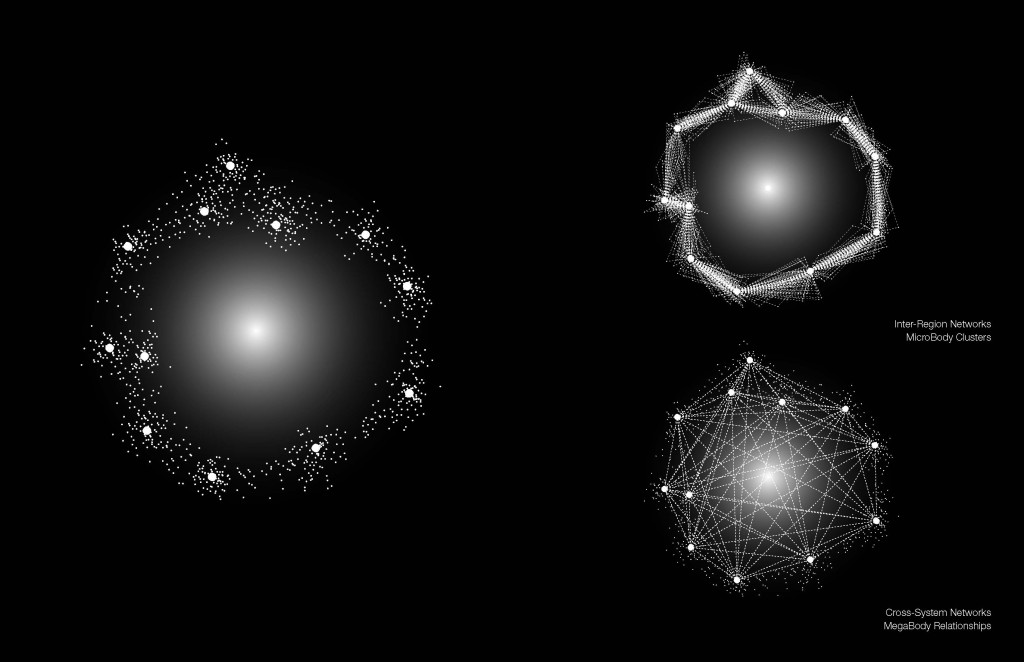

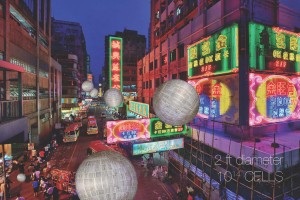

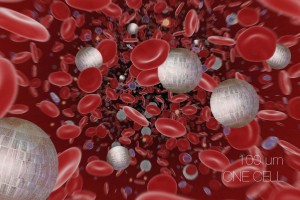

At the scale of a cell, drones are deployed. A swarm of ‘smart’ cells coursing through the bloodstream, engaging the “massive-addressability” of our physiology. Health status is monitored in real time, managed and evaluated by a local network. Changes in blood pressure, heart rate, nutrient quantities, bacterial and viral exposure, and so on are tracked constantly. The average citizen can check their daily health status as easily as they check their email. Many traditional physical medical diagnostics are replaced by expert analysis of changes in data gathered over a lifetime. The majority of health problems are detected and treatment begins long before symptoms manifest. Drugs are designed with chemical tags — drones pick up the drug, access corresponding directions uploaded to the network, and deliver them to the specified body systems. In a society where smart particles measure and archive the health data of most citizens, the biology of entire populations can be managed. The detection of outbreaks occurs within two degrees of infection. Heart attacks are detected instantly — help is dispatched before symptoms even arise. At any given moment, the health and location of each inhabitant is known. Life expectancy and general health skyrocket.

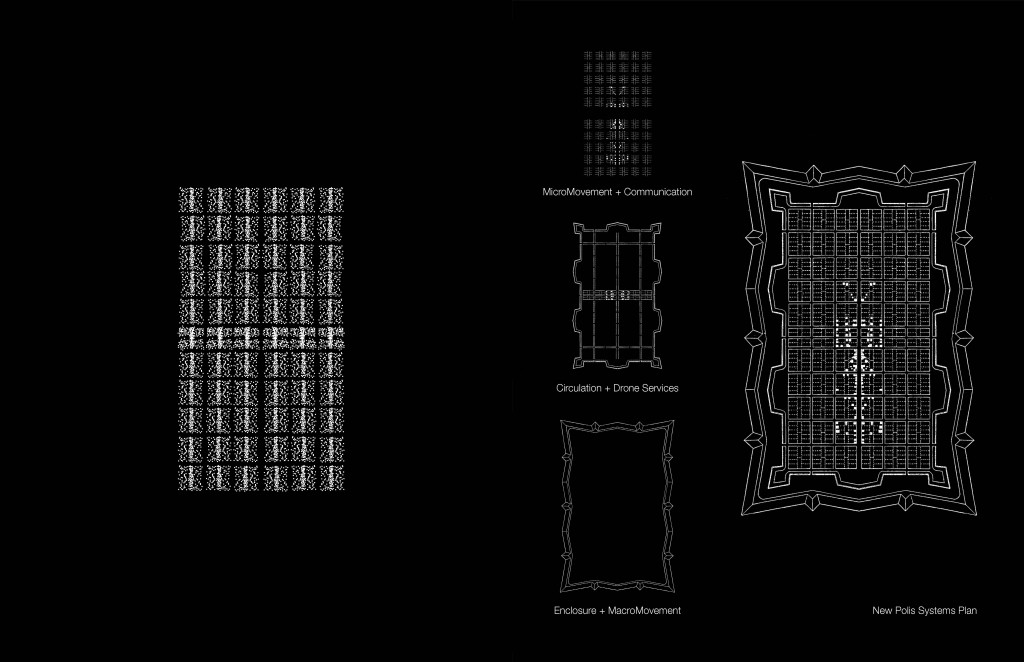

Traffic systems are managed by city-wide networks, using location data gathered from cell-scale drones to optimize travel routes. Urban systems designed to manage waste, electricity, water, transportation, crime, fire, disease, etc, are carried out largely by drones, constantly connected to each city’s network mind. The both the physical and network infrastructure of the city is transformed to accommodate what is, essentially, a new species living in symbiosis with the human population. The majority of human societies are freed from the burden of labor-intensive tasks. The fundamental architectural question — what does it mean to live together? — is evolving at break-neck pace.

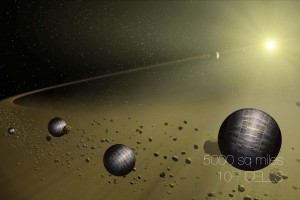

Like Archigram’s Walking City, human settlements are mobile, no longer bound to geography. Entire cities can migrate in response to changing climate, resource needs, population fluctuations, and so on. The settlement growth and needs, tracked in detail by each city, inform the movements of macro-scale drones. Hyper-efficient bodies, perhaps at the scale of entire planets, orbit and gather energy from the sun. The future earth has many moons — designed, built, deployed, and populated. Future exploration and colonization occurs as entire cities migrate outward into the void.

Baobab Urgency

So, as the little prince described it to me, I have made a drawing of that planet. I do not much like to take the tone of a moralist. But the danger of the baobabs is so little understood, and such considerable risks would be run by anyone who might get lost on an asteroid, that for once I am breaking through my reserve. “Children,” I say plainly, “watch out for the baobabs!”

My friends, like myself, have been skirting this danger for a long time, without ever knowing it; and so it is for them that I have worked so hard over this drawing. The lesson which I pass on by this means is worth all the trouble it has cost me.

Perhaps you will ask me, “Why are there no other drawing in this book as magnificent and impressive as this drawing of the baobabs?”

The reply is simple. I have tried. But with the others I have not been successful. When I made the drawing of the baobabs I was carried beyond myself by the inspiring force of urgent necessity.

This is a baobab on Earth:

On the planet of the little prince, this poses the threat of a planetary ecological disaster:

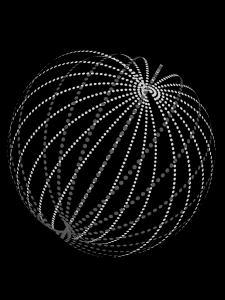

In Antoine de Saint-Exupéry’s The Little Prince and Watts’s The Island, the authors present a profound relationship between scale and ecology. Watts’s Dyson-Sphere organism proposes a model for a species that operates at the scale (in terms of size, energy, computation, etc…) of a massive star, while the Little Prince occupies a world in which a baobab tree is a radical planetary mega-structure. As the territory of architecture continues to expand, one can imagine the role of the designer evolving rapidly to address levels of information and scales previously inaccessible to us. Fundamental architectural questions like, for instance, how an architecture meets the ground, become fundamentally transformed if the designer can engage landscape at the scale of the cell, or deploy intelligent and adaptive building materials. At moments, it requires the relentless enthusiasm of hard SciFi, or the refreshing simplicity of a children’s book, to release us from our intellectual blinders and reveal the questions we will address in the frighteningly-near future. And, with metaphorical baobab disasters lurking around the corner, designers must anticipate what times bring and recognize that the stakes have never been higher.

Without Precedent

When this truly began, where to mark DAY ONE of this brave new epoch, is up for debate. Most historians and scientists might point to the Industrial Revolution. Beginning in the late 1700’s and ramping up to critical momentum by 1850, the Industrial Revolution marks a radical shift in the relationship between human civilization and the environment which has only accelerated. However, as far back as 2000 years ago (and earlier), early civilizations were already reshaping the planet. From the Roman Empire to the early Chinese dynasties, the first significant societies took part in ecologically transformative activities — large-scale agriculture, mining, logging, and so on, in ways that dramatically altered local conditions. Some scientists and historians, like Erle Ellis, have spent entire careers researching far-reaching and widespread effects of human development. It is no coincidence most of these practices grew out of a desire to control energy and resources. This intellectual thread will continue quite clearly through this studio’s research, but also traces the framework of human history.

When asked what geological event could be said to mark the Anthropocene, Dr. David Grinspoon pointed to a particular technology — the first tests of the Atomic Bomb:

…the symbolism is so potent — the moment we grasped that terrible promethean fire that, uncontrolled, could consume the world…

The same hunger for technology that drives modern life and is held up as a solution to climate change, has simultaneously produced works of awesome violence and drives the engine of ever-growing energy demand. In a contemporary culture that worships and fetishizes Technology, there is a strategic delusion in the public mind that divorces our beloved gadgets from this ever-increasing, climate crisis. (Of course even calling this a ‘crisis’ implies a grouping with our present collection of crises: ‘crisis’ in Syria, the economic ‘crisis’ in America, the ‘crisis’ of the Middle Class, etc… Perhaps we should change our vocabulary and call this condition what it really is — a global catastrophe? a both moral and intellectual failure? the next mass-extinction event?)

All that has truly changed in the last 2000 years of human history and works, is scale. Surging from the local and momentary, to the planetary and indelible — we have arrived at our present moment. And it is truly a MOMENT, in geological terms, which could be snuffed out with unfeeling swiftness. For the first time in the history of the species, our economic, religious, cultural, social, and political practices/beliefs have the capacity to change the ecology and geology of the planet. Political decisions that appear to be about energy policy and resource management, reach into the deep structure of the planet. Seemingly everyday social stances on disposable consumer products could preserve, or radically alter, natural systems. And the decisions we now make, as a community, as a nation, and as a species, will lay out the blueprint of our future history.